Ruth’s Ring

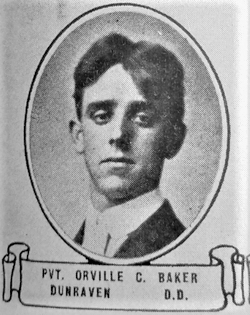

His grandmother’s diamond ring on Michael’s finger. Not worth much in dollars and cents, but the story of its recovery is “worth a million bucks.”

Michael Fairbairn is obsessed with looking for old stuff. He’s spent countless hours over many years scouring farm dumps and river banks, barn ruins and abandoned reservoir towns for small treasures that he carefully catalogues, tangible pieces of history that give him pleasure and cause him to wonder.

His most recent find took his hobby to new heights, or shall we say new lows: a diamond ring that has spent nearly 80 years in the bottom of a septic tank.

It started with a conversation with his aunt, Martha Fairbairn Tait, who revealed for the first time a secret she had kept since was three years old: She had dropped her mother’s engagement ring down the bathroom sink drain. “I was told to leave that ring alone, but I guess I just couldn’t do that. One day I was playing around the sink and I don’t remember if I was wearing it or if it just fell, I just remember I dropped the ring. And there was no stopper in the drain. I never told a soul.”

Not her sister. Or her brother. Certainly not her mother, Ruth Fairbairn, who never once mentioned the missing ring. “I don’t know if my mom thought she’d lost it or what.” So it was something of a relief to finally tell someone – her nephew, Michael.

“She told me she’d always felt bad about it. So I decided I was going to try to find that ring,” he related.

With his daughter Sarah and a pair of shovels, he set off to the site of the former Fairbairn house in Dunraven. The house was torn down in the mid-1950s, but he knew the site, knew where the septic tank was, and he and Amy started digging. It was slow going, but on the third day of digging past the collapsed tank cover, six feet down, he hit pay dirt, so to speak: well-composted sludge, otherwise known as very old poop.

Michael, neck deep in the stone-ringed tank.

Neck deep in the hole, he began to shovel the compost through a strainer. Many shovelfuls later, he saw something shiny, and there it was – Ruth’s ring, last seen by his mischievous toddler aunt so long ago. He wiped it clean, took a photo of it, and sent it to Martha who identified the white gold ring with the tiny diamond in the center.

“I knew he’d find it,” Martha said, “but what were the chances?”

Glad she had come clean with her secret, and thrilled that the ring had been reclaimed, she told Michael to keep it as a family heirloom. One with an amazing story of loss and rediscovery.