“’La Grippe,’ or the Russian Influenza, is heard from all parts of the world and creates the greatest public interest,” reported the Delaware Gazette January 1, 1890. “The fatal cases are very few, but the number of cases is very great and many of them very distressing. There seems to be none yet in this region.”

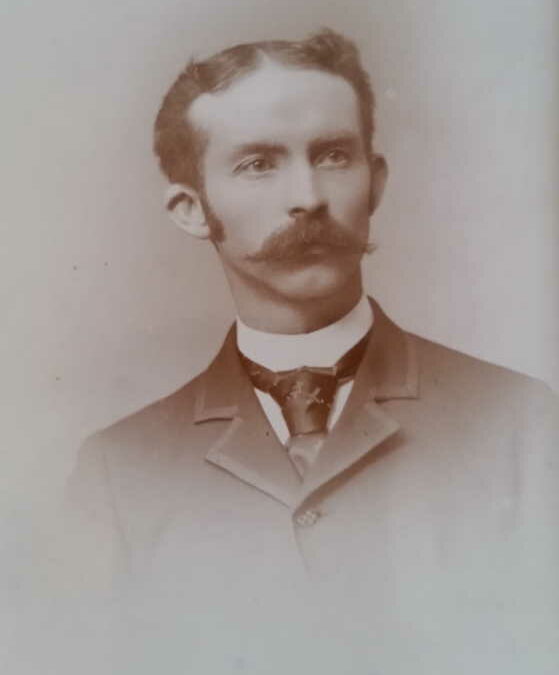

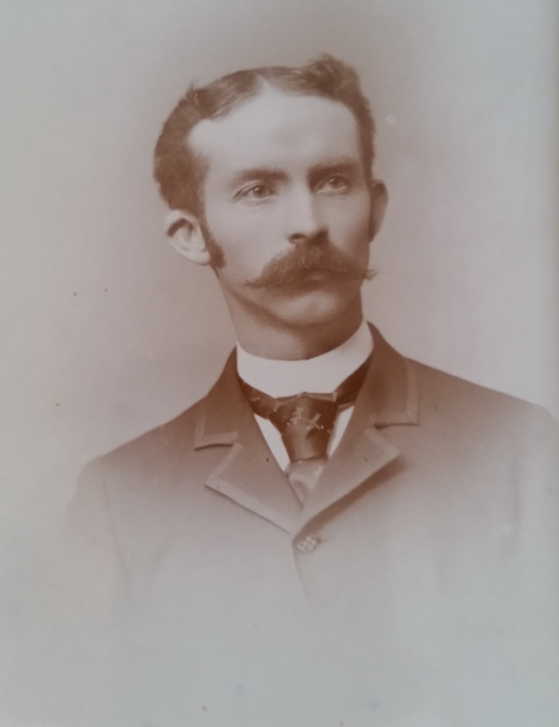

Just two weeks later the Delhi correspondent of the Hobart Independent claimed “nearly every family in this community has been suffering more or less with the prevailing epidemic. Several hundred cases have come under the doctors’ care.” At least one proved fatal – Norwood Bowne, the editor of the Delaware Express newspaper for 51 years, died of bronchitis which took over where the flu left off.

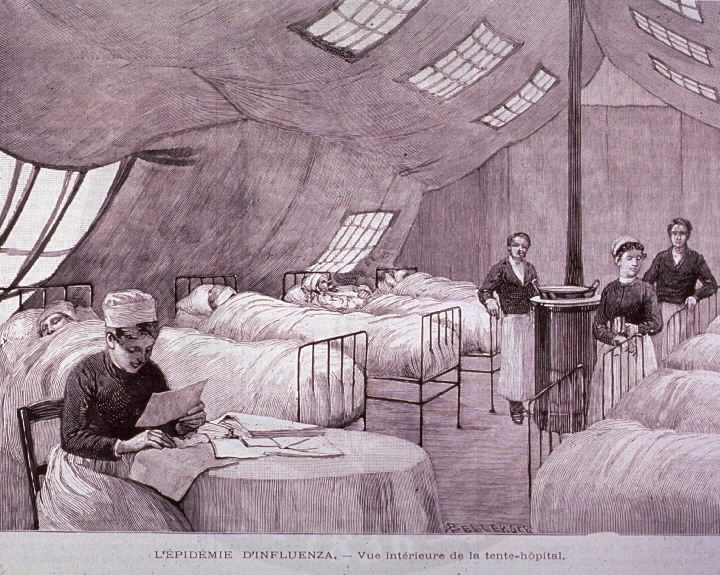

Bowne was among one million people who died in the 1889 pandemic, which began in Russia and spread rapidly throughout Europe aided by railroads and steam ships. It reached North America in December 1889 and spread to Latin America and Asia in February 1890.

Locally, the illness claimed bank presidents, teachers, laborers and physicians. In a time when people were accustomed to periodic epidemics – diptheria, meningitis, typhus, scarlet fever – there was a ho-hum, dismissive tone in some of the accounts. Said the Delaware Gazette January 8, 1890, “La Grippe has become such a fashionable disease that very many have already laid claim to the distinction of having been afflicted with it. Many have colds and suffer greatly, but weather is favorable for such cases, and if a new name had not been introduced we would all be suffering in the good old fashioned way and that would be about the end of the matter.”

Then as now, fear and misinformation spread as quickly as the virus. A report about a Sidney man being taken to the Utica Insane Asylum noted “It is said La Grippe is the cause of his mental derangement.” Another article declared “It is no longer good manners for a gentleman to raise his hat when he meets a lady on the street . . . uncovering the head in the open air (has) caused a number of cases of influenza.”